Why Is It So Hard to Talk Politics with Loved Ones? Learn 5 simple skills to keep your cool in political discussions this holiday season.

Photo by cloudvisual on Unsplash

It’s the yearly holiday party, and I’m enjoying the smell of the Christmas tree, a festive drink, and time spent with family and friends. Suddenly, I am caught unawares by a political comment from Uncle Joe that makes my blood boil. I ‘lose it’ and instantly react, plunging us into an argument. Voices rise, logic goes out the window, us vs. them views dominate. I feel a tightness in my chest, a burning in my belly. For some reason, it feels like the stakes are a lot higher than a dinner conversation, and more like his political beliefs are a direct threat to my world.

Does that situation sound familiar? Do you also lose it in these moments? Does your loved one lose it? Both of you? If so, you are not alone. Conversations about politics and social issues can get volatile and ugly, fast! For this reason, most folks just avoid them. However, as the world around us becomes increasingly divided, I believe it’s more important than ever to find ways to engage in difficult conversations from a place of curiosity and wellbeing, rather than from fear, anger, or distress. As psychologist Eileen Kennedy-Moore (2020) stated, “If people who like or love each other can’t discuss their differences, what hope is there for our country?”

So, after my holiday debacle with Uncle Joe I began to ask myself:

Why do many folks (including me) get so intensely activated by differing political or social opinions?

Why can’t we calmly consider opinions, facts, or data that go against our beliefs?

Most importantly, how can we learn to discuss differing political views without losing it?

To find answers to these questions, I looked to neuroscience.

THE TRIBAL BRAIN

According to neuroscientific research, it turns out our brains are wired, at least in part, to become intensely activated when our beliefs are challenged (Kaplan, Gimbel, & Harris, 2016). Prevailing research in social psychology has shown that when our deeply held beliefs are questioned, especially beliefs related to social identity, we tend to experience uncomfortable negative emotions. To reduce these uncomfortable sensations and feelings, folks will do just about anything, including “rationalizing, forming counterarguments, socially validating their beliefs, ignoring evidence, or discounting the source” (as cited in Kaplan, et al., 2016).

Building on these social theories of “belief maintenance” (Kaplan, et al., 2016), some neuroscientists hypothesize that the neural systems connected to our sense of self- and social-identity, and to our intrinsic sense of physical safety and survival, are the ones driving our resistance to belief change (Kaplan et al., 2016). In other words, although our species has evolved in exponential ways, parts of our brains still largely operate as if we are a tribal species fending against a directly hostile environment. (Think attacking marauders or saber-tooth tigers).

THE STUDY

To test this hypothesis, neuroscientists at the Brain and Creativity Institute at USC set out to study what happens in the brain when strong beliefs are challenged, specifically which neural systems are involved in maintaining strong beliefs in the face of counterevidence (Kaplan, et al., 2016). Researchers performed functional MRIs on 40 strongly identified liberals. As subjects were scanned, they were shown statements that they strongly believed in, some political and some non-political. Then they were shown a series of counterarguments, then the original statement again. They were given a scale to rate the strength of their beliefs before and after the scan, and this was used to measure belief change. From this the scientists could compare what was happening in the brains of folks who were more resistant to change, and those who were more open to change.

Below is a very brief summary of the study’s findings and my takeaways from it, in laymen’s terms. If you’re interested in reading the entire published study, click here.

THE RESULTS

The results were incredibly interesting! First, the study showed that when presented with counterarguments against political beliefs, areas of the brain strongly related to our sense of social identity and “protected values” (Kaplan et al., 2016) lit up. These areas have a powerful role in making sense and meaning and identifying our place in the world. In other words, making sense of our perceived reality. Alternatively, when presented with arguments against non-political beliefs, the MRIs showed increased activity in the parts of the brain related to cognitive flexibility and “reversal learning” (Kaplan et al., 2016), essentially the ability to take in information and adjust our views to accept and understand a new reality.

More importantly, findings suggested that those who had more rigid political stances showed increased activity in the amygdala and the insula, the unconscious areas of the brain that assess for risk. Alternatively, those who had less rigidity in their political stances showed less activity in the amygdala and insula and more activity in the part of the brain related to cognitive flexibility and reverse learning (Kaplan et al., 2016).

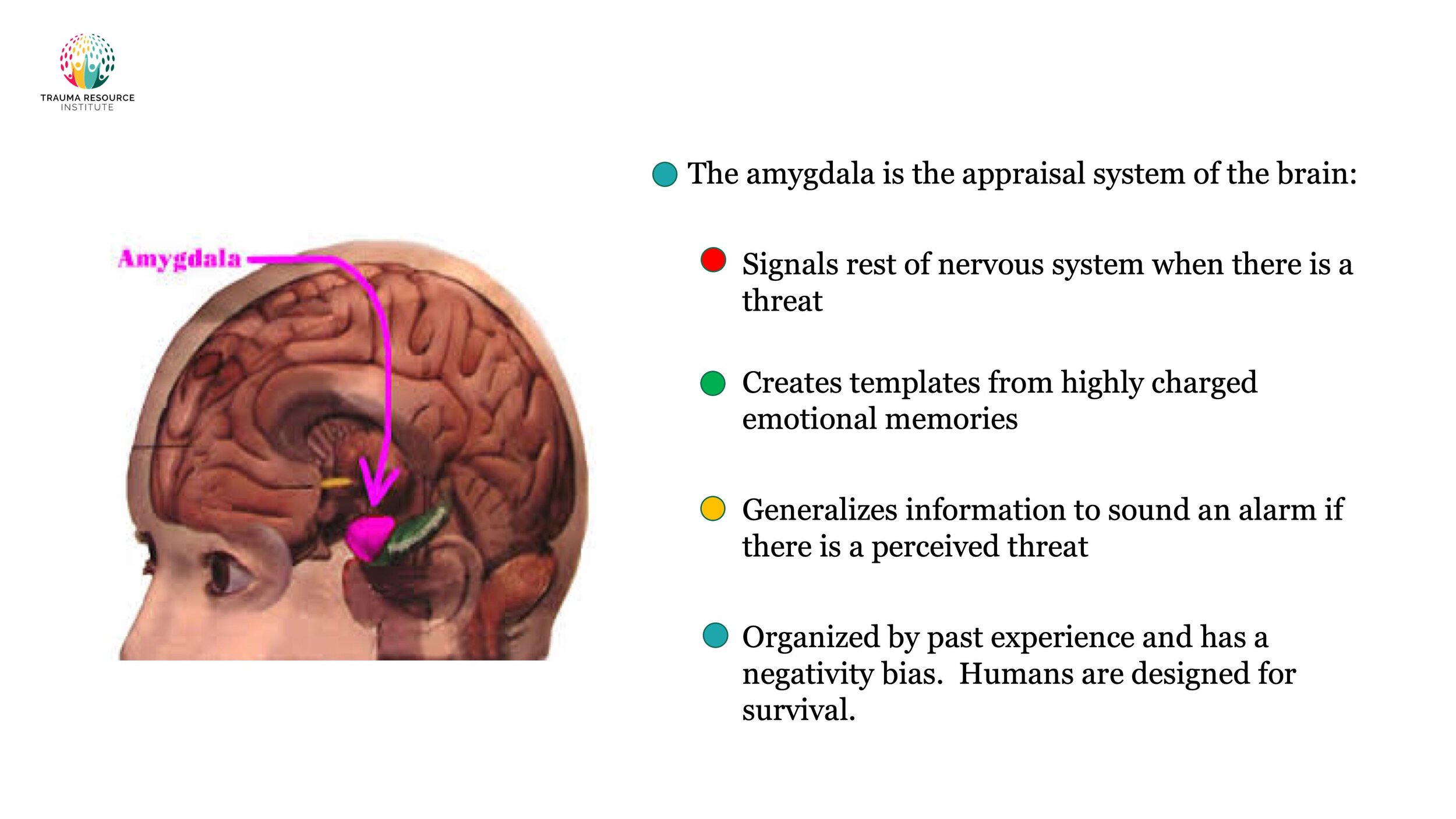

THE AMYGDALA AND THE LIMBIC BRAIN

Basically, humans have the lovely mental flexibility that allows us to open ourselves to new information, to change our minds, and come to new understandings. However, this ability can become hampered if we perceive new information or opinions as a threat to our sense of safety or belonging. Think of the brain as having three parts, the survival brain (the brain stem), the emotional (limbic) brain which includes the amygdala, and the thinking brain (the cortex). Essentially, the flexible, thinking part of the brain can go ‘offline’ if the survival/emotional areas of the brain are activated (Karas, 2021).

Check out the diagrams below:

(Karas, 2021)

(Karas, 2021)

Additionally, trauma research suggests that for some folks, depending on epigenetics and life experiences, the cognitive brain’s capacity for flexible thinking is lower, or the limbic area has a lower distress tolerance, and that will impact the rigidity of a person’s thinking (Shields, Sazma, & Yonelinas, 2016; Ji & Wang, 2018; Van der Kolk, 2014, p. 145). Alternatively, some folks, depending on epigenetics and life experiences, have more capacity for cognitive flexibility and/or higher stress tolerance in the limbic brain, and thus have more flexibility to effectively consider challenging information or opinions (Van der Kolk, 2014, p. 145).

For example, I have a pretty flexible cognitive brain. However, I am epigenetically predisposed to anxiety, meaning my limbic brain has a lower stress tolerance. (Hence my tendency to lose my cool at family gatherings.) But, if I can keep my amygdala from setting off excessive alarm bells, I am better able to listen to and discuss other points of view even if I am totally opposed to them.

THAT’S ME (OR MY UNCLE JOE!) WHAT CAN I DO ABOUT IT?

You might be thinking, “Ok, Michelle, it’s great to know why all this is happening. But how does that help me at Thanksgiving dinner when I feel like I’m going to lose it with Uncle Joe?” The answer is simple, though maybe not easy, at first. If we want to be able to rationally converse with others to find a path together toward a better world, we need to tweak the wiring in our brain to catch up with evolution! We need to cultivate resilient, flexible cognitive brains, AND cultivate well-regulated survival/limbic brains. Then we can listen and communicate from a place of empathy and curiosity, not fear and defensiveness.

The good news is that the brain has what’s called “neural plasticity,” meaning we can re-route our wiring by developing new neural pathways (Karas, 2015, p. 7). Even better news, there are simple skills we can learn to bring our brains back into balance, and expand our own, and others’, capacity for empathy and curiosity. There are many ways to learn skills such as these, my favorite way is with the Community Resilience Model.

THE COMMUNITY RESILIENCE MODEL (CRM)

Developed by trauma and somatic therapy expert Elaine Miller-Karas, LCSW, CRM is designed to teach individuals ways to increase their own resilience and to help others in their community to do so as well. CRM does this by teaching people about their natural, biological responses to stressful situations, and by teaching easy to learn skills aimed at empowering individuals to respond, rather than react, to stressful events (like Thanksgiving dinner with Uncle Joe).

Resilience is quite the buzzword these days, for better or worse, and might bring up a wide range of definitions and reactions. So, to clarify how the word ‘resilience’ is used in CRM, resilience is defined as: “an individual’s and community’s ability to identify and use individual and collective strengths in living fully in the present moment, and to thrive while managing the activities of daily living” (Karas, 2021). Or, in reference to dinner with Uncle Joe, one’s ability to stay “calm and in control when faced with a challenge” (as cited in Karas, 2021).

THE RESILIENT ZONE

Using CRM, individuals can learn to track and identify sensations related to a state of well-being, what CRM calls “the resilient zone” (Karas, 2021), thereby soothing their amygdala and allowing the cognitive brain to remain online and flexible. In the resilient zone, we can feel our emotions fully while still operating from our best self. This ‘zone’ can also be called the ‘Ok Zone,’ meaning we can be 'Ok’ happy, ‘Ok’ sad, or ‘Ok’ frustrated. Or the ‘relational zone,’ meaning when we are in our zone, we are able to fully connect and relate with others, and when we are out of our zone we disconnect, become defensive, and move out of relationship and into isolation.

As part of our elegant biological design, all humans have a resilient zone (Karas, 2021). And we all, as humans, can get bumped out of it. By remaining in our zone, or getting back in when we are bumped out, we can maintain our own sense of wellbeing, as well as stay in relationship with other humans. And it is only from a place of relationship that we can foster empathy, greater understanding, and positive change.

PUT YOUR OXYGEN MASK ON FIRST AND GET INTO YOUR RESILIENT ZONE!

Everyone is sitting around the dinner table, digging into the holiday feast. Someone, already with a tinge of tension in their voice, offers a strong opinion on a recent topic in the news. Hoping for, perhaps, feelings of belonging and safety from their ‘tribe.’ The comment, however, hits you in the stomach like a ton of bricks. Your chest tightens, you feel a burning sensation. They press you for your opinion. It’s bound to escalate. What do you do now?

When two people are in survival mode, that is a recipe for dis-connection. Both parties start to feel defensive, and the flexible areas of the brain go offline. So, what can we do in moments like these? The answer is to maintain our resilient zone or get back into it if we have been bumped out. There is no way to engage in relating if we are out of our zone. So, to quote the advice of airline emergency safety cards, “put your [resilience] mask on first” before you say a word!

HERE ARE 5 QUICK WAYS TO GET BACK INTO YOUR ZONE:

Take a slow sip of water (or juice etc.). Notice the temperature and texture of the liquid in your mouth. Notice the sensations of it going down your throat. The sensation of swallowing. Is it pleasant? Unpleasant? Neutral? If it’s pleasant or neutral, maybe take another sip. Notice what happens on the inside as you do this. Does your heart slow down a little? Does the pressure ease in your chest? Does your stomach relax? Or not? **The benefit of this skill is twofold. You get an opportunity to cool down your amygdala and get a moment to pause before speaking. You can’t say anything you’ll regret if your mouth is full of water!

Look around the room, paying attention to anything pleasant that catches your eye. Take a moment to really notice the details. Notice if anything happens on the inside as you do this.

Count backwards in your head from 10 to 1. Too easy? Then count backwards from 20 in 2s or 3s. Notice what happens on the inside.

Notice the texture of furniture or surfaces in your environment, the feel of the chair cushion or the table you're sitting at. Notice if it is rough, smooth, hard, soft. No surfaces handy? Then notice the texture of your own clothes against your skin or take a moment to brush back your hair or rub your chin. (It will look like a casual gesture, but really you are regulating your limbic system!)

None of these working? Ok, you’ve tried the above skills but are still feeling heated. No problem. Excuse yourself to ‘go to the restroom’ or ‘make a phone-call’, and then find a spot to take a short mindful moment. Take a walk and pay attention to the movement of your arms and legs. Notice the way your feet make contact with the earth. When you feel grounded again, go back to the party!

By using these simple skills, we can ground in the present moment, soothe our nervous-system, and send a message to the amygdala that there is no actual danger. When the amygdala is soothed, we are in our zone, and the full power of our flexible, cognitive brain is online and available to us!

From our zone, we are more capable to experience curiosity, empathy, and compassion, to hear another viewpoint and spend a minute walking in someone else’s shoes. We are also more capable of clear thinking and clear expression of our views with less emotional heat behind our words. So that the listener is less likely to feel attacked and bumped out of their zone.

Most importantly, from our resilient zone we also have the capacity to co-regulate with others to help them come back into their zones. As we track and regulate our own nervous system, we can also track the other’s nervous system through body language. If we sense that another might be getting bumped out of their zone, we might offer a resilience focused reflection or question. A resilience focused question is a non-judgmental, open-ended question that invites someone to bring their awareness to facets of wellbeing or resilience in their story.

SOUNDS AMAZING, BUT HOW DOES THAT WORK IN REAL LIFE?

You might be thinking, “Ok, that sounds great, but how does that actually work?” Let’s look at my conversation with Uncle Joe as an example. He began to talk about Trump and God and Black Lives Matter. I became tense. He pressed me. I lost it. But what would have happened if I used my resilience skills? Let’s imagine:

Uncle Joe begins to talk about Trump and God and Black Lives Matter.

I use my CRM skills to regulate. I track sensations of distress in my body, the tightness in my stomach, increased heart rate. I notice my feet on the floor, my weight in the chair. I take a sip of water and slowly swallow.

Once I’m aware of increased sensations of wellbeing, I empathetically reflect on the importance of religion and faith for him and offer some resilience questions, such as, “I hear how faith has an important place in your life. When did you come to know your faith? How has it helped you in hard times?”

From here, we move away from the general, ideological realm and into the personal, relational realm. He tells stories of his childhood, of how he has felt the presence of God throughout his life, and how his faith sustained him in difficult times.

From my state of resilience, I empathize with him and the sense of safety and support his faith brings him. I begin to understand how disturbing it must feel to have his beliefs and sense of identity challenged by this paradigm shift our world is struggling through. From my resilient zone, I can also find space to join with him, sharing my own story of how the divine (named differently but the same thing) has shown up in my life to carry me through hard times.

Alright, crisis averted! I soothe my amygdala, and Uncle Joe’s, and I learn something new about him which helps me understand him a little better. I also manage to change the subject! Nice move. But is that it? I believe we can also use these skills to make even the tiniest dent in the divisive walls America is building for itself. Let’s imagine further…

From my state of resilience, I track Uncle Joe’s non-verbal cues to see if he is feeling relaxed and safe enough to entertain some new points of view.

If he seems open, I reflect on how faith supports so many of us in these hard times, and how the Church acts as a pillar for many communities. I reflect on how faith is supporting the Black Community as their churches get shot up, or the Jewish community as their Synagogues are defiled by extremists. (I know Joe well enough not to bring up Mosques just yet.)

Perhaps in this way, we can place politics on the backburner and simply experience our mutual human compassion for a moment, stepping away from ‘right/wrong,’ ‘good/bad,’ or ‘left/right,’ to simply reflect on our common humanity. Perhaps no minds are fully changed, but two people are connecting, and it’s much harder to ‘other’ those with whom we are connected.

WANT TO LEARN MORE SKILLS TO STAY IN YOUR ZONE?

The above example is admittedly an ideal, and honestly, I still haven’t managed to keep my cool with Uncle Joe. However, using these skills I have engaged in powerfully meaningful conversations with my parents and other relatives. To stay in our resilient zone and engage in difficult conversations might sound simple, but it is no easy task! Like any worthwhile endeavor, it takes practice, but the payoff is immense. For myself, I realized that when I am in my resilient zone, my need to be absolutely right disappears. As my need to be right abates, I find that curiosity, empathy, and compassion take its place. The best part is, I have discovered that, over time, the more often I am able to stay in my zone, the more often my loved ones start to become more curious and compassionate as well, and to even consider alternative ideas.

As you can see, I love these skills, and want to share them with as many folks as possible. So, if you would like to learn CRM, here are some options:

Join a CRM Resilience and Relational Skills Group at my private practice for a sliding scale fee. These groups are NOT therapy! (Though they may feel therapeutic.) The groups are a place where you can learn and practice the skills in a safe, supportive space. Once you learn the skills, you become a CRM GUIDE, and can share the skills with your loved ones, teach them to your kids, or support a friend through a crisis. Click here to find out more.

Take a CRM workshop at the Trauma Resiliency Institute (TRI). Are you so interested that you want to take a training at TRI? Go for it! There are 1 day, 2 day, and full week trainings. Here is a link to their website where you can learn more.

Do more research on CRM. Curious and want to find out more about what CRM is and how it works? Click here for links to information, articles, and the latest research on how CRM is supporting some of our most oppressed and stressed communities.

CONCLUSION

We all have a brain and a nervous system, so it is inevitable that all of us will get triggered at some point by the divisive viewpoints of others. But I, along with the neuroscientists at USC, believe that the only way forward is to foster relationship between humans (Kaplan et al., 2016), not divisive ideologies. Because the more divided we are, the easier it is to vilify and de-humanize others. Yet if we are in relationship, connected, it is easier to feel each other’s humanity, and to hold empathy and compassion for each other. As Father Gregory Boyle wrote, “Close both eyes; see with the other one. Then we are no longer saddled by the burden of our persistent judgments, our ceaseless withholding, our constant exclusion. Our sphere has widened, and we find ourselves, quite unexpectedly in a new, expansive location, in a place of endless acceptance and infinite love” (2010, p. 145). I may never get to “endless acceptance and infinite love,” but I can, with practice, find more empathy and connectedness in all my relationships, and maybe, just maybe, help change this world a little bit for the better. Would you like to join me?

Michelle

References

Boyle, G. (2010) Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Ji, S., Wang, H. A study of the relationship between adverse childhood experiences, life events, and executive function among college students in China. Psicol. Refl. Crít. 31, 28 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-018-0107-y

Kaplan, J.T., Gimbel, S.I., & Harris, S. (2016) Neural Correlates of Maintaining One’s Political Beliefs in the Face of Counterevidence. Scientific Reports 6, 39589. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39589

Karas, E. (2021, July 15) The Community Resiliency Model. [Powerpoint Slides]. Claremont, CA: Trauma Resource Institute.

Karas, E. (2015) Building Resilience to Trauma: The Trauma and Community Resiliency Models. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kennedy-Moore, E. (2020) Handling Political Disagreements in the Family: When Family Members Have Different Political Views, How Can You Keep the Peace? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/growing-friendships/202011/handling-political-disagreements-in-the-family

Shields, G. S., Sazma, M. A., & Yonelinas, A. P. (2016). The effects of acute stress on core executive functions: A meta-analysis and comparison with cortisol. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 68, 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.038

Van der Kolk, B. (2014) The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York, NY: Penguin Books.